In recent years, just outside of Bossier, Louisiana, the Red Chute Bayou Levee has been repeatedly threatened by major floods. Two of these significant flood threats required close to five miles of sandbagging to prevent the levees being overtopped. These

emergency efforts are incredibly expensive and require significant emergency preparation efforts from the surrounding communities and the U.S. Army National Guard.

To reduce the flooding risk to nearby communities, we’re conducting ongoing analysis to simulate previous floods and determine whether or not it’s worthwhile to raise the levee. In order to make the best decision, we built a model that could

look at watershed-wide impacts of raising the levee under a variety of conditions.

One of the many regulated structures found in the Red Chute Bayou watershed. Pictured is the Red Chute Bayou Cross Bayou structure used to regulate flow with the Flat River.

Building the Model

Due to this being a regulated levee constructed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, we expanded our scope to adhere to the standards and procedures they require under a Section 408 review. Under this guidance, we analyzed the impact of raising the levee

and set up a detailed model to understand the project.

The hydrologic aspect of the model was developed to simulate both observed and frequency rainfall runoff. We used radar reflectively data to estimate rainfall totals by adjusting to data found in the local network of rain gages. The results of the hydrologic

model using observed rainfall data were then compared to observed stream gage runoff from the 2009 and 2016 floods.

After building our calibration model, our next step was to go through the process of determining the discharge runoff for multiple flood frequencies. We looked at both 100- and 500-year flood models to help compare the current and proposed conditions

of raising the levee. Our primary focus was on any increase in the water surface elevation or increase in flood inundation areas. A secondary concern was the potential to change the quantity of available flood storage and subsequently increase flooding

downstream of the proposed project.

Challenges in Model Development

One of the main challenges in developing our model was in converting to a 1D-2D combined model analysis from the established 1D model used by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The difference between 1D and 2D models is that 1D models are based on steady

state conditions, which wouldn’t provide us with the accurate information we required related to flood volumes. To solve this data gap, we expanded and generated a combined 1D and 2D model in which the channel was modeled using the 1D features

and 2D overbanks. Using this combined 1D-2D model resulted in significantly increased model runtime. For this particular project, we went from about a one minute run time for the 1D models to upwards of two hours for the 2D models. Other challenges

with the expanded model included greater likelihood for model instability and increased time spent troubleshooting.

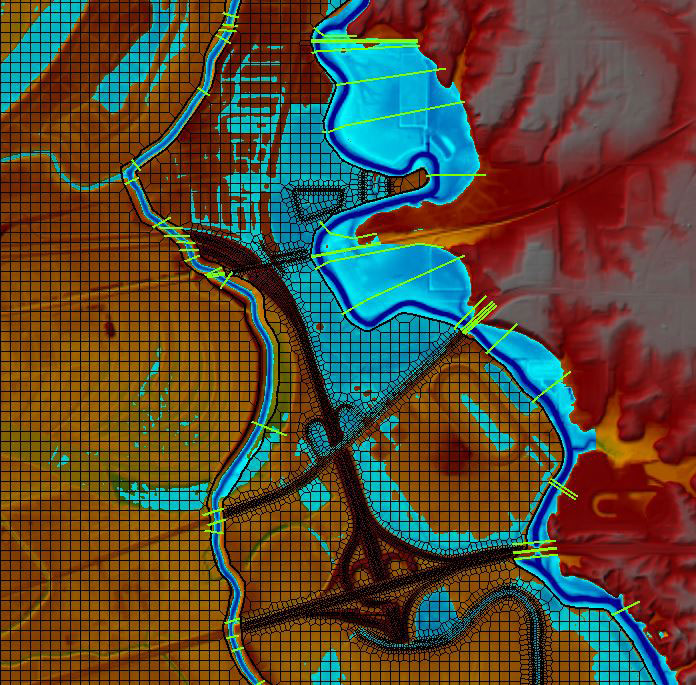

Results from HEC-RAS 1D/2D combined model showing flood depths from one of the many flood scenarios.

Lessons Learned for Future Projects

In building our models and analyzing the Red Chute Bayou we came away with three primary findings which will help us to better serve clients in future regulated watershed projects.

- 1. Basic rainfall runoff models may not produce the discharge frequencies needed to understand the associated flood risks. We determined that a traditional HEC-HMS model wasn’t going to work because of the strict regulations and large size of

the watershed. This led us to other methods such as rain gage adjusted radar reflectivity. Additionally, we switched from a traditional hydrologic routing in HEC-HMS to estimating the routing conditions in the hydraulic HEC-RAS model.

- 2. Watersheds with significant regulation may require supporting gage records to determine flood risks. In essence, we couldn’t have done the study without the gage data.

- 3. Stakeholders should explore similar methods to understanding the characteristics of their regulated watersheds to assist in future planning and flood mitigation.

Ultimately, in a regulated watershed like the Red Chute Bayou Levee, traditional hydrologic and hydraulic studies won’t be reliable in understanding the flood risk.