Surveyors who originally crossed the U.S. looked a lot different than the modern surveyor. These frontiersmen carried survival equipment along with their chains, compasses, and theodolites (an instrument used to measure horizontal and vertical angles). They marked territory by notching trees and placing boulder piles, and ran property lines along small brooks and streams.

Early American boundaries still show up today as references for the work we do, but the rough tools used hundreds of years ago weren't quite as accurate as today's sensitive equipment. Their old chains expanded and retracted based on the temperature and barometric pressure, while present-day GPS units use dozens of satellites to mark our precise horizontal and vertical location.

During this year's National Surveyors Week, I'd like to pay homage to the early American surveyors and to the men and women retracing those boundaries today.

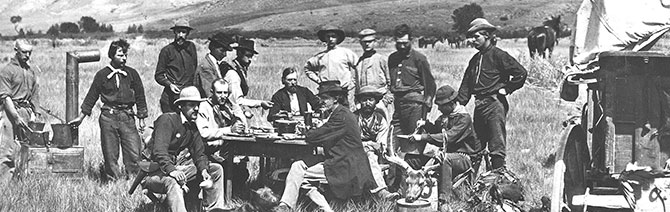

A 1870 U.S. Geological and Geophysical Survey camp at Red Buttes, Wyoming Territory. Photograph courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey.

A Weatherworn Deed and an Ancient Tree

Surveying new land is a rare opportunity. Nearly the entire nation has been mapped at least once, and our job mostly involves retracing the last person's plots to improve accuracy, verify property lines, or subdivide parcels of land. In most cases, the last surveyors passed through just a few months ahead of us, but every now and then the last surveyor was an original frontiersmen. In these cases, finding boundary markers becomes a difficult challenge.

Retracing an original survey means finding the original landmarks, natural elements that can change drastically over the course of generations. In one case, my team was given an old deed—a weatherworn document that referenced trees as property corners. We had trouble finding one, but along the perimeter was a rotted stump containing hundreds of rings. On a hunch, we carefully removed a sample and sent it to a lab for identification, only to find out it was the exact tree species we were looking for.

An Enduring Point of Reference

When we’re able to accurately identify these historic boundaries, we monument the corners to make sure the next surveyor doesn't miss it. This may involve placing a permanent marker—similar to the brass National Geodetic Survey (NGS) disk below—to represent the exact point of reference. A more famous example is the Four Corners Monument, which marks the precise point where Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah intersect. Once placed, we record each monument's horizontal and vertical location, run levels to and from adjacent monuments, and send these coordinates to an agency like NGS or the Bureau of Land Management.

With nearly four million square miles in the U.S., there’s a lot of retracing yet to be done. Some can be accomplished at the individual level (like my tree story above); other cases require far more coordinated efforts (like the Alaska remapping project). No matter the scope, it's always exciting to sight the same lines as one of the first surveyors.